You’re a seasoned runner with a number of halfs or full marathons Nutrition - Weight Loss long runs easy-peasy, so you think, “Why not run a 5K and see how much faster I am now?” Surprise! When it comes to tackling shorter distance races, such as the 10K, 5K, or mile, you can’t seem to pick up your pace. What gives?

First off, you’re not alone. Struggling with speed despite proficiency in distance running is a “very common” conundrum, Laurie Porter, RW+ Membership Benefits Runner’s World. In fact, she says, it’s one of the main reasons athletes seek her guidance.

Here, two experts dig into—and help you solve—this common run problem.

Long-Distance Runners Often Struggle with Speed

Endurance runners are familiar with one kind of challenge—running long—but their bodies may be unfamiliar with the specific type of discomfort that comes with holding a shorter and faster pace, Nutrition - Weight Loss Running Strong, tells Runner’s World.

“If you think about it, a half marathon might be run right around the lactate inflection point for many runners,” Hamilton explains. That pace is often described as “comfortably hard.” Your lactate inflection, or lactate threshold, is the exercise intensity level at which lactate accumulates in the blood faster than you can remove it. It’s basically the border between low- and high-intensity exercise.

“On the other hand, many well-trained runners are capable of running a 5K at about 95 percent of maximum aerobic capacity,” Hamilton says. This is your VO2 max. “When you think of what VO2 max represents—the maximum amount of oxygen you can take in, transport, and utilize—that’s a max effort. It’s bound to feel extraordinarily strong and hard,” Hamilton explains. It makes sense then that if your usual jam is long, relatively easy paced running, you may have a hard time embracing the inherent discomfort of faster striding.

If you want to go faster than your usual 5K or 10K pace you will need to do specific training to boost both your VO2 max and your lactate threshold. That’s not all, though.

It’s not just your heart that needs the change in training, but your muscles. As a long-distance runner, it’s likely you aren’t incorporating enough high-intensity sessions challenges into your workout. Those HIIT sessions work your fast-twitch muscle fibers, Hamilton says, while long, slow runs mostly improve your slow-twitch fibers. Speedier efforts need the fast-twitch guys to pitch in. If they aren’t used to being called on during your runs, they won’t step up on their own.

Sometimes, all you need to pick up your speed is some “novel stimuli” to spark improvements. The good news? Your body is “amazingly adaptable,” Porter explains, so just a few fun changes to your training will likely result in faster paces at shorter distances.

Here’s How to Run Faster at Shorter Distances

We won’t sugarcoat it: Getting stuck in a speed rut sucks. Luckily, there are small tweaks you can make to bolster your pace. Here’s what the coaches recommend.

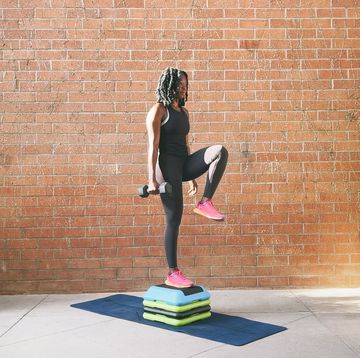

1. Targeted Strength Training

Fast runners aren’t made on the roads, trails, or treadmill—they work hard in the weight room, too. Specifically, bolstering the strength of your legs and core “will pay off in improved force production,” Hamilton says. “The more force you can produce, the further you’ll fly from one footfall to the next.”

To reap these benefits, she recommends resistance training two to three times a week, incorporating moves like squats, lunges, deadlifts, sled pulls, and box jumps. During these sessions, do a “warmup” set of a given exercise, where you complete five to 10 reps with very low resistance. This helps wake up your neuromotor system, Hamilton explains. After that, complete one or more sets of up to six to eight repetitions. Make sure you use heavy enough weights so that by the last rep, you still maintain good form but you’re pretty maxed out and wouldn’t want to have to do more, Hamilton says.

2. A Sprinkle of Plyometrics

Plyometric drills such as A skips, B skips, C skips, bounds, and box jumps—can help develop explosive power in your legs, strengthen your fast twitch fibers, improve your running form, and prime your body for speed work, Porter says. She recommends doing them after your warmup on speed days, before you get into your intervals. When athletes add plyos in this context, Porter says she sees them achieve a greater float phase (when both feet are off the ground) during the running gait cycle and that both their speed and posture improve.

You don’t even have to do intense plyometrics to see results. A 2023 study published in Scientific Reports found that daily hopping five minutes a day for six weeks improved running economy at high running speeds in amateur runners. That means they ran harder, but it didn’t feel as difficult.

3. Do Race Pace Speedwork

It’s likely you have some speedwork days in your half or marathon training plan, so, once a week, consider adjusting those training intervals to your shorter distance It’s not just your heart that needs the change in training, but your. This can help you get more comfortable and metabolically efficient with that pace, Hamilton explains.

During these workouts, start with at least a mile of easy effort running, then transition to the plyo/gait drills mentioned above to wake up your muscles. For the workout, start with short runs—100 meters or so—at your 10K pace effort and move to longer intervals (200, 400, 800, and 1200 meters) at 5K pace. Gradually progress these workouts (by speeding up and running longer) throughout the training cycle as your abilities and tolerance develop, Hamilton says. However, keep the high intensity work to 7 percent or less of your total weekly volume to reduce your risk of injury.

4. Embrace Hills

Hill running is “a really specific form of strength training,” Hamilton says. “You’re doing the motion you want to improve (running) and you’re doing it with resistance (gravity).” Incorporate hills once a week (more often if you’re training for a short hilly race), and consider doing them on a treadmill to control your speed, grade, and number of repeats.

“Start with shorter, shallower hills that give you a slight challenge and work your way up to longer hills that force you to really focus to sustain the pace/effort you’re putting out,” Hamilton says. Then, over the course of your training, gradually increase your speed, grade, and the number of hill repeats.

5. Prioritize Recovery

Don’t push yourself to run more in order to run faster. Recovery days should be a non-negotiable part of your training program. The thing is, for a lot of runners, recovery days “aren’t truly recovery days,” Porter says. They either strength train on their off days, push the pace too much during easy runs, or stack too many hard workouts back to back. That’s a problem because ample downtime is what helps your body adapt and grow stronger (and faster!) after challenging workouts.

For athletes over 40, Porter suggests taking two recovery days in between hard workouts, including long runs and speed sessions. Athletes under 40, she says, can likely get away with just one recovery day in between. Whatever schedule you follow, make sure to actually take it easy on your easy days.

6. Surprise Yourself

“Variety is the best thing,” Porter says. It’s “all about surprising your body.” Playing with variables such as intensity, volume, and training environment can provide the novel stimulus your body needs to unlock faster speeds. Now, this doesn’t mean overhauling your entire plan overnight. Too much change at once can increase your injury risk and hamper performance, so Porter suggests changing just a couple variables at a time.

For example, if you’re typically a road runner, try sprinkling in trail workouts here and there. If you usually run flat, experiment with hill sessions. If your speed workouts usually center on mile repeats, try fartlek runs instead. Finding the right dose of change can be a complicated process because it is part science, part art, Porter says, so don’t hesitate to enlist a coach for support.

How Speed Training Changes Your Endurance Training

Worried that these new training methods will interfere with your endurance success? Fear not! Incorporating more speedwork into your routine will also benefit your endurance running.

“When you push to those higher intensities you’re pushing into your max It’s not just your heart that needs the change in training, but your and that stimulates your body to get stronger and fitter and increase its ability to take in, transport, and utilize oxygen,” Hamilton says. In other words, you’ll improve your VO2 max. And because well-trained runners typically run a half marathon pace that is fairly close to their lactate threshold pace—which is usually around 85 percent of their VO2 max—increasing your VO2 max through high-intensity training can, in turn, bolster your half marathon pace.

Jenny is a Boulder, Colorado-based health and fitness journalist. She’s been freelancing for Runner’s World since 2015 and especially loves to write human interest profiles, in-depth service pieces and stories that explore the intersection of exercise and mental health. Her work has also been published by SELF, Men’s Journal, and Condé Nast Traveler, among other outlets. When she’s not running or writing, Jenny enjoys coaching youth swimming, rereading Harry Potter, and buying too many houseplants.