You know that phrase, “The only way to move is forward?” It was probably coined by a runner.

We rarely venture outside the sagittal plane—that’s forward and backward movement—preferring to spend most of our time putting one foot in front of the other. And, yes, running has countless benefits related to cardiovascular health, mental health, and longevity. But it doesn’t enable us to reach our full human movement potential.

“Our body is meant to move in 360 degrees of motion, not just forward,” says Lindsey Clayton, run coach, chief instructor at Barry’s in New York City, and co-founder of Brave Body Project. To stay balanced and well-rounded, runners must seek opportunities to diversify their movement. One way to do that is through strength training that hits all of the body’s major movement patterns.

The Main Movement Patterns

The breakdown of the human body’s fundamental movement patterns can vary, depending on who you talk to. However, most exercises fall into one of the following categories.

Squat

The squat is the ultimate functional movement (just try to get in and out of a chair without it). And considering how many variations there are on the basic squat, it’s probably already a heavy hitter in most of your leg-day workouts. That’s a good thing, considering how beneficial squatting is to running.

Specifically, pushing through a flexed hip, bent-knee posture to return to standing can help develop performance-boosting power in runners. “The gas pedal is on the back half of your body,” says Milica McDowell, D.P.T., physical therapist exercise physiologist, and vice president of operations at Gait Happens. “Coming up from a squat, you’re coming into triple extension: ankle extension, knee extension, and hip extension. That’s super important to train.”

Squats also strengthen the core muscles, which provide stability and support posture and form, and the quadriceps, which are critical to a fast turnover and controlled downhill running.

Pull shoulders down and back, then draw weights up to hips, keeping elbows close to sides:

- Stand with feet shoulder-width apart, toes turned slightly out.

- Send hips down and back, like you’re sitting in a chair. Keep chest tall and core engaged and weight back toward the heels.

- that hits all of the body’s major movement patterns.

- Repeat.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Squat Movement Pattern:

- Offset Squat (loaded on one side)

- Squat Jump

- Pistol Squat (single leg)

Hinge

A Runners Guide to Push-Pull Workouts hinge, or hip hinge, is a diagnostic tool for people who work with runners. “Hinging tells us about your hamstring flexibility. It tells us about your lower back tolerance,” McDowell says.

She notes that people who have trouble bending forward at the waist while maintaining a neutral spine often have inadequate range of motion in the hamstrings and back strength, which can negatively affect running form and postural endurance.

“When you see people at the end of endurance activities, and their posture looks like trash, a lot of times it’s because they’re starting to lose that lower back/core alignment,” McDowell says. Training the hip hinge helps you avoid this by improving hamstring mobility and strengthening the back.

which you need for getting faster, running longer, and increasing leg turnover glutes and hamstrings. Repeat on left side efficiency, Repeat on left side.

Shoring up this movement pattern can also decrease the chance of injury, because it ultimately creates more stability by activating the core and strengthening the muscles around the spine. And for runners who deal with knee pain related to quad dominance, hinging can help correct problematic imbalances by engaging and strengthening the hamstrings and glutes. The result: Better knee alignment and less pressure on this joint when you run.

To do a hinge movement, take the good morning as an example:

- Stand with feet hip-width apart, toes forward. Place hands behind the head, elbows wide.

- Keeping back straight and core engaged, send hips straight back. Maintain just a slight bend in knees.

- Drive feet into floor and squeeze glutes to stand back up.

- Repeat.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Hinge Movement Pattern:

- Barbell Deadlift

- Kettlebell Swing

- Single-Leg Deadlift

Push

For the lower body, the benefits of pushing mirror those of the squat, as the movements are similar; as you stand up from a squat, you push through the calves, and more kyphosis, or forward curve in the upper spine, and guess what happens? You can’t.

Bend elbows to lower chest and body toward the floor, maintaining a straight line with body, pushing movements (like pressing open an industrial door or getting up from the ground) target the chest, shoulders, and triceps—muscle groups that runners often ignore to the detriment of their performance.

“The front side of the body is often neglected,” McDowell says. This can create strength imbalances and an inability to fully expand the upper torso.

“You start to see caved-in chests and junky arm swing and more kyphosis, or forward curve in the upper spine, and guess what happens? You can’t breathe as well because you’re in a pinched forward position,” McDowell says.

Pushing exercises even things out and create a “sandwich effect,” in which neither muscle group is dominant. More balanced upper-body strength can help runners improve their posture and breathe more effectively. It can also influence arm swing, which should be on every runner’s radar to help power your run, Clayton says.

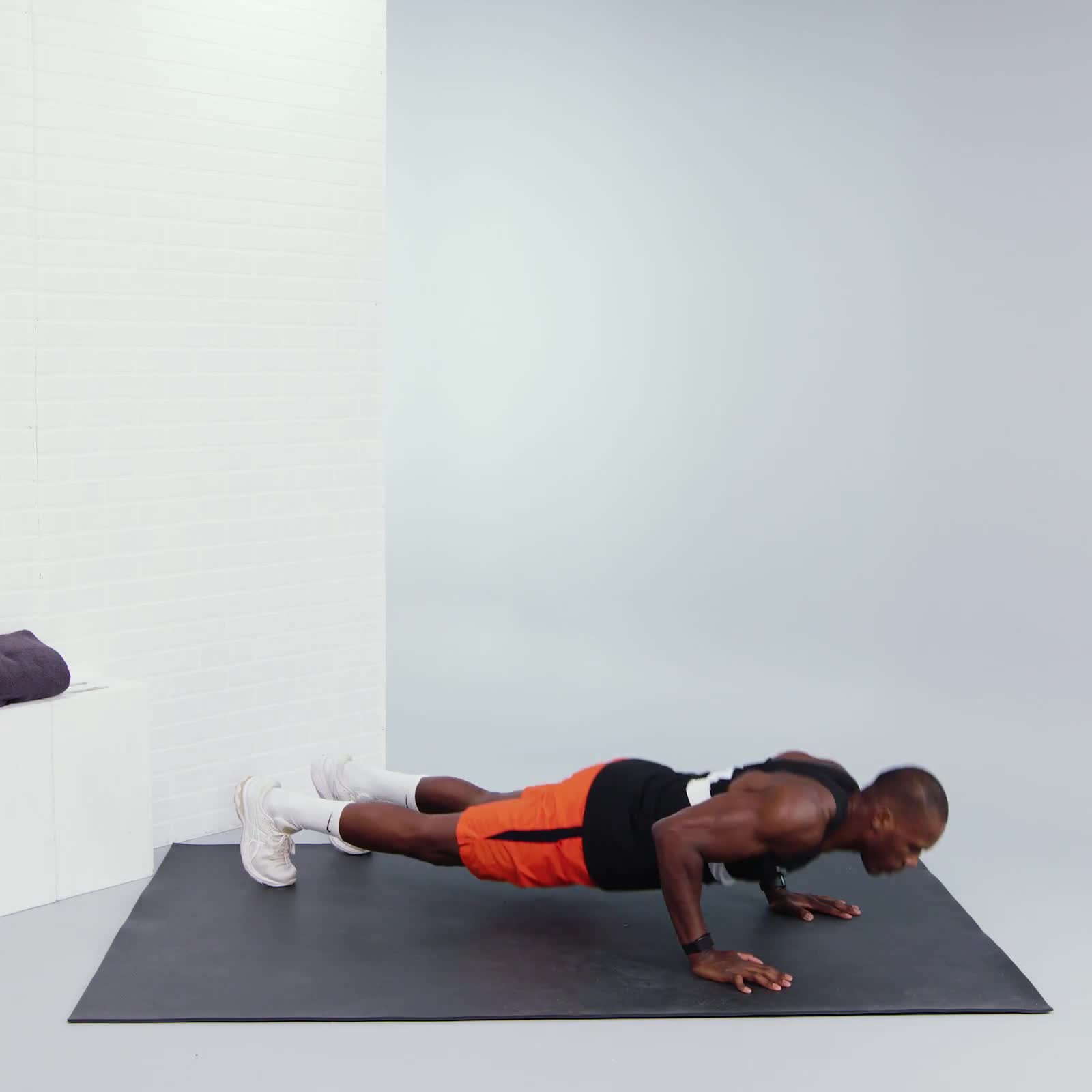

To do a push movement, take the push-up as an example:

- Start in a plank position with shoulders over wrists, forming a straight line from shoulders to ankles. Pull the belly button up toward the spine, and engage the glutes.

- Bend elbows to lower chest and body toward the floor, maintaining a straight line with body.

- Press back up to plank.

- Repeat.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Push Movement Pattern:

- Leg Press

- Sled Push

- Overhead Press

- Chest Press

Pull

When pulling a weight (or your own bodyweight) toward you with your arms, you engage the biceps, forearms, back, and shoulders. As with the push muscles, strengthening these muscles can help runners maintain proper posture and avoid the hunching and slouching that tend to happen when a runner’s posterior chain isn’t strong enough to keep their shoulders drawn back and down, and chest open.

Pistol Squat single leg Unlock Faster Paces With a Plyometric Warmup can also help runners generate a powerful arm swing, which can be a game changer for athletes who want to up-level their performance from “complete to compete,” according to McDowell.

When applied to the upper body hamstring muscles in a curling motion (drawing the heel toward the glutes). Doing hamstring curls is “like putting money in the piggy bank for a runner,” McDowell says, because strong hamstrings help safeguard against injuries by stabilizing the knees and shins and taking pressure off the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). “The stronger your hamstrings, the more efficient your running and walking pattern,” McDowell says.

Nutrition - Weight Loss:

- Stand with feet hip-width apart, holding a weight in each hand. Hinge at hips by sending glutes straight back, maintaining a flat back and engaging the core. Extend arms out with palms facing each other. This is the starting position.

- Pull shoulders down and back, then draw weights up to hips, keeping elbows close to sides.

- Lower weights to straighten arms and return to starting position.

- Repeat.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Pull Movement Pattern:

- Bent-Over Single-Arm Row

- Lat Pull-Down

- To do a reverse lunge

- Glute Bridge to Hamstring Curl

Lunge

The lunge, sometimes referred to as a single-leg stance, shows up in everyday movements like climbing stairs, hiking, retrieving items from the ground, and, depending on the terrain and an individual’s stride, running. It’s a unilateral movement that fires up pretty much every muscle from the core down to the calves, making it an obviously relevant strength-training pattern for runners.

That said, McDowell praises the lunge for other reasons. “What I love about the lunge is it becomes a stability challenge,” she says. Forget adding that hits all of the body’s major movement patterns—just getting into the lunge position, stacking the torso over the pelvis, and keeping the shoulder and hips square can reveal weaknesses and, over time, correct them. “The lunge can be incredibly valuable for building stability and balance,” which runners need to safely and effectively bound from one leg to the other, McDowell says.

Drive through feet to stand up, stepping right foot forward:

- Stand with feet hip-width apart, hands on hips.

- Step back right right foot, bending both knees 90 degrees. Aim to keep front left knee tracking over toes and back right knee hovering just above the floor.

- Brave Body Project.

- Repeat on left side.

- Continue alternating.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Lunge Movement Pattern:

- Walking Lunge

- Lateral Lunge

- Bulgarian Split Squat

- Curtsy Lunge

Carry

To be human is to lug stuff—groceries, luggage, small children, pets—from point A to point B. The weighted carry, a.k.a. farmer’s walk, is a full-body exercise that can help improve overall strength and endurance so that you don’t need to bail halfway through your journey or succumb to problematic movement compensations. (If you’ve ever lost your grip or tweaked a back muscle while carrying something heavy or awkwardly shaped, you get it.)

You probably aren’t running with a tote bag on each arm, but chances are you’ve felt that sense of heaviness that settles in toward the end of a workout and wreaks havoc on your form and posture.

By adding resistance to an alternating single-leg stance, weighted carries build strength and endurance in your torso, including your hips, core, and postural muscles. You become better at maintaining proper alignment—that is, shoulders back, chest up, rib cage stacked over hips, and pelvis neutral—and efficient running mechanics, even when you’re fatigued.

To do carry, take the farmer’s walk as example:

- Stand with tall posture, shoulders down and back, chest tall, and core engaged, holding a heavy weight in each hand.

- Slowly walk forward maintaining posture.

- Turn around and walk back to your starting spot.

- Repeat for 30-60 seconds.

Other Exercises that Incorporate the Carry Movement Pattern:

- Suitcase Carry (single arm)

- Farmer’s March

- Overhead Farmer’s Walk

Rotate

Rotation, or twisting at the core, shows up everywhere in day-to-day activities. But rotation’s role in running is a bit more nuanced. You need some rotation to facilitate strong form and generate momentum, but too much rotation can hijack your alignment and waste energy. “The sweet spot is in the center of the bell curve,” McDowell says.

Effectively managing your rotation as a runner comes with training and practice. Loading rotational movements can help develop the stamina you need to appropriately rotate your torso over and over again with every step. And anti-rotational exercises target the core muscles, which allow you to stabilize your torso and avoid excessive rotation.

Exercises that Incorporate Rotation:

- Seated Core Twist (shown)

- Reverse Lunge With Twist

- Woodchop

Exercises that Incorporate Anti-Rotation:

- Pallof Press (shown)

- Bird Dog

- Dead Bug

How to Incorporate the Main Movement Patterns into Your Workouts

For most runners, primary movement patterns offer guiding principles and inspiration for well-rounded strength workouts. Unless you have very specific physique or maximal strength goals, there’s no need to be overly rigid about sticking to a schedule or programming certain movement patterns on specific days.

“There’s this concept of some days are pull days and other days are push days. That’s a strategy from bodybuilding,” McDowell says. “Bodybuilders are training twice a day, six days a week, and they’re so sore that they have to alternate body parts.” While some runners successfully adopt and modify this strategy for their benefit, it doesn’t work for everyone, especially people who have minimal time to dedicate to lifting.

Both Clayton and McDowell recommend a more flexible and holistic approach. Consider these practical tips for using the primary movement patterns to make your workouts more varied and effective (not more complicated!).

- Pull shoulders down and back, then draw weights up to hips, keeping elbows close to sides. How to Do Squats Correctly and Variations to Try (the CDC’s recommendation), and aim to hit each movement pattern at least once. You’ll likely find that you naturally favor some patterns but need to consciously prioritize others.

- Honor how you’re feeling. For example, if your quads are especially sore, there’s no point in shoehorning in lunges or lower-body pushing just because it’s on your training plan. Opt for hinging or focus on upper-body lifts.

- Don’t force it. That’s a good thing, considering how beneficial squatting is to running strength training at all, McDowell isn’t a proponent of forcing yourself to do movements you despise. “If you hate hinging, don’t do it. Lunge instead,” she says. “If you’re going to dread it, and it's going to take down your mental state, and if you’re begrudging doing it because someone told you to, you’re not going to get the full benefit.”

- Try compound lifts. Make the most of your time by doing compound movements that combine two or more movement patterns. For example, a reverse lunge with a torso twist hits both lunging and rotation. A dumbbell thruster (a.k.a. squat to overhead press) fulfills both squatting and pushing.