BY ALL ACCOUNTS, IT WAS A PERFECT DAY TO GO FOR A RUN.

On the first Sunday morning in October 1972, Central Park was bathed in early fall sunshine, the crisp 50-degree air giving the changing leaves on the sugar maples and Sawtooth oaks near Tavern on the Green a bit of a sheen as the third New York City Marathon was scheduled to go off. It doesn’t feel right using an uppercase M with this marathon. At the time the race was decidedly small-scale. Only 278 runners had signed up (for this year’s race on November 4, some 47,000 have entered), they paid just $1 to get in (instead of today’s $255), and the entire 26.2-mile race took place within the confines of the park, whereas today’s marathon stretches over five boroughs and requires the space of Central Park just to stage the start. And Fred Lebow, who would ultimately become the impresario of the world’s largest race, had yet to make a name for himself beyond the city’s small and chummy running fraternity.

But perhaps suggestive of his P. T. Barnum–like skills, Lebow had persuaded The New York Times and a few other dailies to come to the park that day. News, Lebow promised, would happen. So the Times sent one of its reporters, Gerald Eskenazi, to cover the race, and Patrick Burns, a Times photographer for nearly 50 years, to shoot it.

Other Hearst Subscriptions.

Shoes & Gear.

Shortly before 11 a.m., the six women entered in the race—yes, just six—lined up at the start. Lebow and his fellow organizers had openly courted women when the first New York City Marathon was held in 1970, even going so far as to ignore rules put in place by the Amateur Athletic Union that barred women from marathon racecourses. For years the AAU, the then-governing body of track and field and distance running and which sanctioned events such as marathons, had been intent on smothering a bubbling interest among women who wanted to run longer and race farther. It did so by disseminating unfounded “scientific” research (for instance, that women who ran more than a few miles risked infertility) and invoking confounding rules to keep women on the sidelines.

But soon after the second New York City Marathon, in the fall of 1971, the AAU relented, somewhat, on its stance: It ruled that “certain women” could take part in marathons, provided they either start their race 10 minutes before or after the men or on a different starting line. The rulings—imposed so women would run a “separate but equal” race from the men—was viewed by many runners of the day, female and male alike, as just the latest act of discrimination enacted by the AAU.

Join Runner's World+ for unlimited access to the best training tips for runners

Five of the six women on the Central Park starting line came from either Manhattan or Long Island. Their running résumés varied to the extreme: One woman had won the Boston Marathon five months earlier; another rarely ran at all. The five were in their late 20s and early 30s, friends or acquaintances who typically met in the park for training runs or to pass time while their husbands or boyfriends raced. The sixth runner was a 17-year-old from the Jersey Shore who had just started college the month before and had little connection to the other five women.

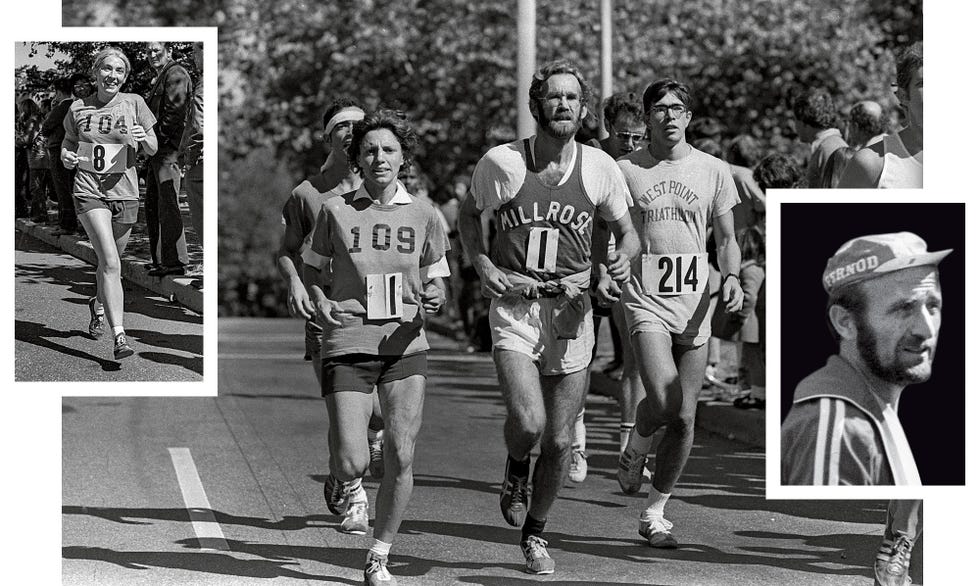

They stepped to the line, near 64th Street and Central Park Drive, and faced south toward Columbus Circle. The 272 men slated to run that day crowded around waiting for the women to get their 10-minute head start. The women, spread across the line side by side, glanced at each other, and over to Lebow standing near the starter.

The gun went off.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below.

Give A Gift.

As Eskenazi reported in the next day’s Times, the six women just sat there “in the lotus position.” They then held up signs mocking the AAU and its discriminatory practices—everyone, that is, but the young runner from the Jersey Shore.

Patrick Burns clicked his camera, taking the photo that would run across four columns of Monday’s Times, and be picked up by other newspapers around the nation, and make the AAU officials go ballistic when they saw it.

BACK IN THE NEW YORK CITY AREA.

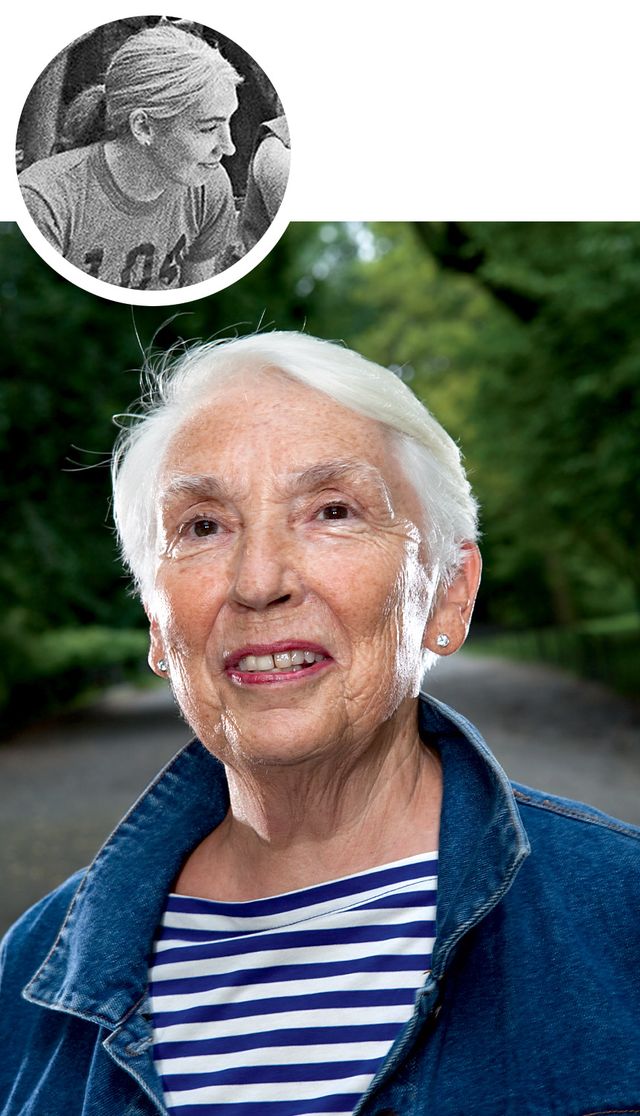

A Part of Hearst Digital Media, bouncing from one pile of papers to a stack of magazines and then to the two-drawer metal filing cabinet stuffed with 40 years’ worth of folders and memories. The way she hustles around the confined space, you wouldn’t know that her knees ache and that she no longer runs. She weighs little more than 114 pounds, her weight in the spring of 1972 when she made history by becoming the first woman to win the Boston Marathon, officially, and her brown hair looks just like it did in the decades-old newspaper clippings she is pulling from the filing cabinet.

She uncovers a folder with press accounts of her landmark Boston victory. “Oh, my!” she says when she sees the front page of the April 18, 1972, edition of the old Boston Record American. It features a half-page photo of a beaming Kuscsik next to the men’s winner, Olavi Suamalainen, both crowned in laurel wreathes. The photo is loaded with meaning, considering its historical context. Just five years earlier, newspapers across the country had run another picture from Boston of another pioneering runner. In that photograph an enraged Jock Semple, Boston’s then race director, is attacking a college student, Kathrine Switzer, as she’s in midstride on the marathon course. At the time women were still banned from the race. But Switzer had managed to get a number and, despite Semple’s best efforts, race to the finish line, becoming the first woman to run Boston with a bib, albeit unofficially. But decades later the lasting image of the 1967 marathon is Semple angrily, desperately reaching out to rip the bib number off of Switzer’s shirt, only to be thwarted by a body block from the runner’s boyfriend.

Now, here was Kuscsik, pixilated in newsprint for much cheerier reasons. Her smile is dulled only by the other big news of the day: “Reds Attack U.S. Ship in Tonkin Gulf” blares the headline atop the Record American’s front page.

Born to Run Back.

Moments later, Kuscsik calls out, “Oh, look at this!” She’s found a yellowed copy of an interview she did with reporter Philip Nobile in the summer of ’72, a few weeks after her Boston win.

What a year it had been. In July Gloria Steinem had launched Ms., the magazine of the brewing feminist movement. In March, after six decades in the making, the Equal Rights Amendment was passed by the U.S. Senate, a bill emblematic of the mounting influences of such voices as Betty Friedan’s and the National Organization of Women. (Ultimately, the amendment failed to get the requisite number of states for ratification.) That spring, Congress also passed Title IX—high schools and colleges could no longer just offer boys’ basketball or men’s soccer. At the time few high schools or colleges offered sports like cross-country and track for women. Title IX would change that, forever.

Yet even with that shifting tide—heck, Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman” topped the charts in 1972—the first question Nobile posed to Kuscsik provides a reminder of the times.

Nobile: “Long-distance running isn’t the most womanly thing a woman can do; all that sweating and grunting, so why do you do it?”

Kuscsik: “Just the way you phrase the question shows your attitude. Who says it is not the most feminine thing a woman can do and who says sweating or grunting isn’t feminine? I have yet to meet a female runner who grunts. Although a lot of men do. Running is neither masculine or feminine. It’s just healthy….”

Viewed through a modern lens, Nobile’s question seems inappropriate if not idiotic. Last year, women accounted for 41 percent of the 518,000 marathon finishers in the United States. This summer, in London, the field in the women’s Olympic Marathon outnumbered the men’s, 118 to 105. But in the early 1970s, Nell Jackson, Ph.D., the head of the AAU’s women’s track-and-field committee, was saying things like, “I wouldn’t give permission to run a marathon. It’s not in the interest of the national program. I’m very concerned about the effects of these distances on females.” The AAU maintained running farther was not only risky but also unladylike. “This was in the back of their minds, that if women injured themselves training too strenuously for these difficult physical activities, they could injure their reproductive organs,” says Sara Mae Berman, a three-time Boston Marathon winner in the unofficial era. “[The AAU] was in the mode of trying to protect girls from being masculinated. Competition where you would sweat was just not proper.”

Kuscsik still rolls her eyes over the stipulation that stated any woman who traveled to an AAU-sanctioned meet “had to be accompanied by a female chaperone.” When Kuscsik first got her AAU card, in 1971, she was the mother of three children, all under age 6. She needed a babysitter, not a chaperone.

Today, the woman who reporters of the era routinely called “the shapely brown-haired mother of three” and “the attractive, diminutive Nina Kuscsik from Long Island” still lives in the same ranch home on a cul-de-sac in South Huntington that she bought with her then-husband, Dick, in 1965. She raised her two sons and daughter here, mostly on her own, and has no plans of moving out anytime soon. “I’m actually thinking about putting in central air-conditioning,” Kuscsik, 73, reveals at one point on a steamy summer afternoon. But it was from this modest home that she nurtured her love for running—and orchestrated the push for equality in the sport of long-distance running.

A competitive cyclist and a speed skater for much of her early life, she took up running in 1967 when she was 28. She had picked up Jogging, the running manual by Bill Bowerman, and read it between loads of laundry. “It said that if a high school girl could run a seven-minute mile, she was worth training, so I went out and ran a 7:05 mile. I was already pregnant (with her third child, Timothy), so I figured I was worth training. I kept running until I was three or four months pregnant. That’s how I got started.” She pauses and picks up her discolored paperback copy of Jogging. “It’s a great book,” she says. “Cost one dollar.”

She returned to running soon after Timothy was born. “I’d get a babysitter, or I’d wait till the kids would go to sleep and I’d run around the block. Six times around was a mile,” she says, giggling at the memory. “I’m running around and around and around. I’d go by the house, just in case I heard anything. I could be inside in 10 seconds if anyone started crying.” When she had a chance to go for longer runs around the neighborhood, patrolling police officers would often stop her. At the time, the late ’60s, a woman didn’t just go out for a run. As Kuscsik explains, “The police thought I was running away from something.”

The new runner became so caught up in the sport that in the spring of 1969, she and Dick drove north to run the Boston Marathon. She knew of the ban on women, but it didn’t bother her at the time. She traveled to Boston not to make trouble, just to compete, and ran the race as a bandit, one of a half-dozen or so unofficial women who snuck onto the course once the men had started off. In her first marathon, she finished in 3:46. She knew only because it was the same time as a male runner she had finished with. Unlike the 1,152 men in the race, Kuscsik left Boston with no official recording that she had taken part.

Other Hearst Subscriptions.

Until that point, she says, she had never felt discriminated against, or at least not because she was a woman. In the ’60s, she didn’t get caught up in the early goings of the women’s-lib movement. She worked as a nurse until her first child came along, and then quit, taking on the familiar role of that era with no complaints. She enjoyed being a housewife and mom, being home, and, if time allowed, the chance to run or bike or skate a bit. She was happy and content. “I wasn’t going out to prove that women could do anything.”

She didn’t see the need. For years Kuscsik had competed in dozens of cycling and skating competitions (she won three New York State titles in 1960), often side by side with men. Sure, she enjoyed winning, but mostly she competed “to accomplish goals. If you could win, that was exciting, but I would always have my goals.” And not once did she get any grief for being a girl, until she had to bandit the Boston Marathon.

“It was like, Women aren’t allowed to run?!” she says, a quizzical look coming across her otherwise serene face. “I thought, This is bad. Who did this? As a woman, this didn’t make sense, that there were all these restrictions.” A pause. “Something,” she says, “had to be done.” Then she looks around her basement.

That Pre Thing following her Boston run, Kuscsik began meeting more and more runners, male and female, who, like herself, were hitting the streets for exercise, camaraderie, a good, hard race—and, for sure, time away from the kids. They connected at races in Yonkers and in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, and went for training runs on a loop not far from the old Yankee Stadium.

This was hardly a boom period for New York, or for the sport of running. Around this time, you had students rioting at Columbia University and inmates taking over Attica. A subway system drenched in grime and graffiti. Frank Serpico ratting out corrupt city police officers. A teetering financial base that, by the mid-’70s, would push the city to the edge of bankruptcy. Central Park was emblematic of the city’s eroding core, as the park developed a notorious reputation as a nexus for crime, not recreation. As for running? Its first mass popular movement wouldn’t kick in until after Frank Shorter’s marathon win at the 1972 Olympics in Munich.

Still, in Manhattan, the outer boroughs, and the suburbs, pockets of die-hard runners had started to form. They included the likes of Ted Corbitt, who as early as the late 1950s was running well beyond marathon length, becoming the best-known ultrarunner in the world. Another celebrated runner was Gary Muhrcke, who was regularly winning area races when he wasn’t rushing to infernos as a member of the New York City Fire Department. In 1970, Muhrcke won the first New York City Marathon, then launched a chain of running-shoe stores in the city and beyond. And there was Vince Chiappetta, a biology professor who was often chided, in a friendly sort of way, by fellow runners for the mask he wore during his workouts. “I could tell you stuff about the air quality in New York at the time that no one else knew,” says Chiappetta, 79, still teaching and running.

Besides being a masked marvel, Chiappetta was also known for collaborating with Lebow on the staging of the first New York City Marathon. The two made for an odd pairing. There was Chiappetta, the academic from the Bronx, steeped in the rules and regulations of running, a cofounder of the Road Runners Club of America, a growing influence in promoting distance running—much to the annoyance of the AAU. Then there was Lebow, the bearded, Manhattan clothes salesman with the heavy Transylvanian accent, who wanted nothing to do with process. “Fred hated going to meetings,” Chiappetta says. “He took care of all the crazy publicity stuff. I didn’t have the time, and really, I couldn’t tell stories like he could, but it worked very nicely for us.” Over the next two decades, after Chiappetta stepped down as codirector, Lebow become the face of New York running, his attention-getting ways and chutzpah turning a meager marathon in Central Park into the biggest race in the world.

But the embryonic running community was far from an all-guys club. “No, we were welcoming to everyone,” says Chiappetta. “We saw no reason women couldn’t or shouldn’t run.”

The women, as it turned out, didn’t need much coaxing. Take Liz Franceschini, a native of London who moved to New York City in 1963, and took a job in sales at Tiffany’s that lasted for 37 years. On weekends, away from the jeweler’s headquarters on Fifth Avenue, Franceschini felt at ease with the “scruffy guys” her husband, David, regularly ran with in Van Cortlandt Park. By 1970, she had enough of watching and began running herself. “I said, ‘You know what? I’m into this,’ and I started training.”

After nearly five decades in the States, Franceschini still speaks with a light British accent—which only adds a cleansing touch to her gritty running tales. “A group of us, including Nina, would run races in the middle of nowhere, up by Yankee Stadium on Sundays,” she says, beginning one story. “And people used to throw things at us—bottles, I think—out of the tenement windows.” She’s laughing now. “There was a men’s locker room along the route—really it was more like a public toilet—where the men would go. But us women had to go, too, and we just said, ‘Hey, guys, get out of here for a minute!’ And we went in and did our thing. They all laughed at us, because they were used to us being around. It was a little clique of people.”

Lynn Blackstone joined the movement around the same time as Franceschini, and for a similar reason: to follow in the running footsteps of her boyfriend (and soon-to-be husband), Dave, a top finisher in the early New York City Marathons. One of Blackstone’s favorite training spots was the Reservoir, on the northern end of Central Park, with its mile and a half running loop. Before Dustin Hoffman made the site famous in the 1976 suspense-thriller Marathon Man, Blackstone ran the Reservoir regularly, befriending Lebow along the way. “Fred would ride his bike up to the park and then run around the Reservoir,” Blackstone recalls. “In those days, you actually knew every runner on the Reservoir by name.” Lebow eventually talked Blackstone into helping him put on Road Runners events, including the one that would launch his stuntman’s reputation: the Crazylegs Mini Marathon, in June of 1972. Lebow, working with Kuscsik and Kathrine Switzer, conceived the Mini to be the first all-female road race, but it gained immediate attention when Lebow brought in a team of Playboy Bunnies to run the early blocks of the 10K race. Forty years on, the black-and-white photos of bunny-eared women next to wide-eyed runners cast an indelible image of the race, and the promoter. “Everything they say about Fred is absolutely true,” says Blackstone, who ran her first race at the inaugural Mini. “Fred was a real visionary. And savvy.”

The Mini would be Jane Muhrcke’s first race, too, a bit of a surprise, perhaps, as she was the wife of a marathon champion. But Jane, at the time a mother of three young kids, says she never took to running. “Every spring I would go out and start to run a little bit,” she says, “but it never stuck.” What lasted were the friendships she developed with Kuscsik, Franceschini, and Blackstone. They’d see each other at races, Jane often offering to watch the Kuscsik kids while Nina raced. Their friendships grew to the point that the women began sharing a summer home together, a rental that included Lebow for a time. In 1972, they watched Shorter’s Olympics win in Jane’s Long Island TV room. Running had brought the women together—and made them reliable partners. “It was almost like there was a race every weekend,” Muhrcke says. “Everybody knew everyone at the races. It was a lot of family time. It was quite a small world.”

And from this small world—from these four women and with a nudge from Lebow, Chiappetta, and a few other male buddies—came an idea that, when executed, on October 1, 1972, changed the face of running forever.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back can make for foggy memories. Details get blurry. The recovery of old documents becomes harder. The friend—or even adversary—you once had is no longer alive to confirm—or deny—what really took place. That’s the nature of recorded history; it’s not always a perfect timeline.

So reconstructing the events of that third New York City Marathon and what happened—and didn’t happen—is as easy as gluing together pieces of a shredded photograph. But after conversations with many individuals who were in Central Park that October morning, here’s the picture that comes into focus:

Nina Kuscsik, Lynn Blackstone, Liz Franceschini, and Jane Muhrcke came to the park armed with a plot to embarrass the AAU. It had been hatched in the weeks leading up to marathon Sunday. Who deserves the credit for conceiving it is the stuff of conjecture. “It probably should go to Nina, who was quite active at that time,” says Franceschini, 72, now living in Maryland. Kuscsik credits Lebow. “I’m sure it was all Fred’s idea,” she says.

Lebow, who died of cancer in 1994, never claimed authorship, but his role is indisputable. He knew that a sit-in, complete with handmade protest signs (“Hey AAU. This is 1972. Wake Up!”; “The AAU is Unfair”), would make a great photo op for his fledgling race, and he coordinated its staging with Kuscsik. Her motivation dated back to her first run in Boston, in 1969. Her frustration with being left out of the official records intensified each time she returned, in 1970 and ’71, as did her enmity for its source. “It wasn’t Boston’s fault we weren’t allowed to run, it was the AAU’s,” she says. “People who were supposed to do something for us weren’t doing anything.” Officials of the tradition-bound Boston followed the body’s mandates, unlike officials in New York, who simply “ignored the AAU,” says Chiappetta.

To change the formula, Kuscsik partnered with Chiappetta and Aldo Scandurra, a longtime competitive runner in New York City and an AAU representative. The two men told Kuscsik that while they could help maneuver legislation through its politburo-like bureaucracy, women had to publicly push the agenda. “That way,” Chiappetta says he told her, “nobody can blame us evil men for forcing you to do things.”

In the fall of 1971, Kuscsik attended the AAU’s national convention in Lake Placid, New York. She had prepared a proposal that called for ending the ban on women in AAU-sanctioned marathons, like Boston’s, and laid out her evidence: No reputable medical research had been produced to show marathoning hurt women; and women were running faster races without any side effects. (Just weeks before the convention, Kuscsik had become the second American woman to run a sub-3:00 marathon.)

Kuscsik took the proposal to Patricia Rico, the AAU’s national women’s chairman. Rico was a former athlete herself, and, well, a woman. But rather than see the wisdom in the women’s pitch, Rico continued to stand by the AAU’s medical premise. As well, she said, she feared women would get an unfair pacing advantage if they ran in men’s races. “Which was ridiculous,” Chiappetta counters. “Our races weren’t that big back then. If we saw a good man slowing down to help a woman, we would have pulled him off the course.”

Before the convention ended, Rico (who died in 2010) and her committee agreed to a compromise of sorts. The AAU raised its maximum distance for sanctioned-women’s races from five miles to 10 miles, and said “certain women” could run the marathon. And what did certain mean? “I still don’t really know,” Kuscsik says. “Essentially we took it to mean any woman who had shown they could run that far.” In return, Rico stipulated that women marathoners had to start from a line separate from the men or begin 10 minutes before or after the men. If that was progress, Kuscsik didn’t see it. “It was still discriminatory. They were setting up two sets of rules.”

Their first implementation came the next April at Boston, which, after 74 years, would now officially accept women. Kuscsik entered with seven other women, including a 17-year-old high-school standout from Spring Lake, New Jersey. For most of her high school career, Pat Barrett trained with the boys’ cross-country and track teams. (Her Catholic high school wouldn’t start a girls’ track team until her junior year.) Still, she managed to clock a 3:24 a month before Boston, beating the then-Boston qualifying time of 3:30—a standard for both men and women. She also caught the eye of a runner nearly twice her age.

“Nina said, ‘If you don’t go to Boston, I’ll break your legs,’” recalls Barrett, now 57. “She was teasing, of course. But she emphasized how important it was to me and for women. As a kid I didn’t understand at the time. I was naïve. But the principal let me out of school to go to Boston—and the nuns were thrilled.”

On marathon morning, the women started from a line drawn a few feet from the men’s start. To Kuscsik and her friends, it signaled a continuing divide. “We were a little peeved,” says Franceschini, who didn’t run that day but had come to support Kuscsik. “It was the age of women wanting to be equal. We didn’t think we should be singled out. That’s why we got upset.”

Not so upset that they didn’t run well: Kuscsik ran 3:10:26, becoming the first woman to officially win Boston; Barrett was 30 minutes behind. Still, enough was enough. It was time to make a public statement.

Sales & Deals, in their runs and other gatherings, Kuscsik persuaded her three friends—Blackstone, Muhrcke, and Franceschini—to sign up for the New York City Marathon, even though none had come close to running that distance. But the idea was not for them to finish the race—it was just to be on the starting line for the protest Kuscsik and Lebow were cooking up. “I sent for my AAU membership card a week before the race just so I could enter,” says Muhrcke, chuckling. “I wanted to support Nina, and after talking to Fred Lebow about it, he was looking for more women to make a statement.”

Two other women, neither of whom was aware of the pending protest, had signed up for the race. One, Cathy Miller, was the girlfriend of Paul Fetscher, a regular among the city’s hard-core runners. “I was dating her at the time,” says Fetscher, 66, a 2:21 marathoner at one point. “She loved coming to races. But she wasn’t serious about it. We dated for a year and then totally lost touch.” (Miller could not be located for this story.) The other was Barrett, now a college freshman. “I drove up with friends from the Jersey Shore just thinking I would run a race,” Barrett says. “Everything kind of caught me by surprise.”

About 30 minutes before the race start, Kuscsik, Muhrcke, and Fetscher huddled near a bench. They quickly scribbled anti-AAU slogans on poster board, which someone—no one can remember who—had brought. In their haste, a few misspellings occurred (“The AAU is Archiac”; “The AAU is Midevil”). At the same time, a petition circulated among the male racers. It read: “As AAU registered Athletes we support the right for women to run in the same race as men, and start at the same gun, regardless are whether or not they are scored separately.” Syntax aside, at least 60 men signed the document.

Minutes before the start, Muhrcke saw Chiappetta, who was still in the dark, and said, “Just to let you know, something’s going on at the start.” The vague warning was fine with Chiappetta. “I didn’t need to know what it was,” he says. “I was just happy the women were doing something.” Soon he, the press, and the 500 or so spectators at the start would find out. The gun sounded, the women sat down, and the posters went up. Shouts of “Chauvinist pigs!” and “Right on!” rang out from the crowd.

And yet, while the sit-in was intended to exorcise the women’s frustration, the scene—as captured in Burns’s photo for the Times—was more love-fest than bra-burning. Most of the men standing behind the women, waiting to run, are smiling. Blackstone, in a striped tank top better suited for a summer picnic than a road race, looks bemused. She’s holding the sign reading “Hey AAU. It’s 1972. Wake Up!” “I don’t know how I got it. Somebody handed it to me,” she recalls. “I was usually more of a background player.”

Muhrcke, seated next to Blackstone in a Superman T-shirt, flashes the brightest smile of the bunch. “We were surprised that there were even photographers there,” she says. “That’s how small it was. It was kind of impromptu and really terribly coordinated.”

The one face among the six that’s difficult to see or read is Barrett’s. She’s between Franceschini and Kuscsik, who has a kerchief in her hair, a mischievous grin on her face, and the sign “AAU is Unfair” in front of her. Barrett, 14 years younger than most of the other women, looks at the ground, as if she’s trying to hide something. After the race, she told Eskenazi of the Times: “I didn’t know what to do. I was just there to run. And anyway, I thought the AAU might do something to me if they saw a picture of me carrying a sign.”

At 11:10, on schedule, the men’s race went off. At that point the women got up and joined them. Photo-op accomplished, Muhrcke, Blackstone, and Franceschini dropped out after less than half a mile. At some point Miller, too, dropped out. Kuscsik and Barrett, though, ran the entire distance—four and a half loops of Central Park. Kuscsik beat Barrett again, to this day still the only woman to win Boston and New York in the same year. Kuscsik ran her 26.2 miles in 3:08; Barrett in 3:19. Or so they thought.

Life of a BQ Squeaker.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below Patrick Burns roamed the streets of New York City, and the world, taking some of the more historic photographs ever to appear in The New York Times. He was in Times Square for the V-J Day celebration in 1945, and was back 20 years later when a melee broke out between protesters from opposing sides of the Vietnam War. Four years later, when the Apollo astronauts paraded up Broadway in 1969, there was the 61-year-old Burns hopping out of the press truck, ignoring restrictions placed on the media, and snagging an up-close shot of the heroes. As a colleague later wrote, “Pat’s exercise in bravado was rewarded the next morning with a six-column picture atop Page 1. On the CBS News that evening, Walter Cronkite held up that very same page, praising the image.”

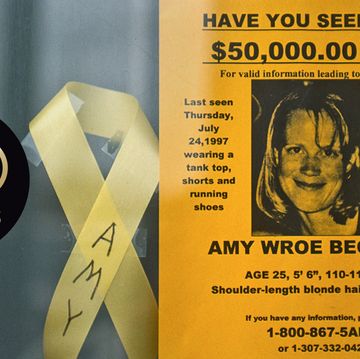

Cronkite never commented on Burns’s photo of the ’72 marathon sit-in, but that doesn’t mean the picture didn’t make waves. “That photo was very important,” Kuscsik says, staring at a copy of it 40 years later. “The publicity that this got—I mean, Pat Rico knew she had no way to beat it.”

In fact when Rico saw the photo the next day, she immediately called Rudy Sablo, the AAU’s top official in New York. Afterward, Sablo phoned Chiappetta. “Rudy says, ‘She’s furious. She wants to throw you out of the AAU,’” Chiappetta says, laughing. “I said, ‘Well, good. I wish she would start the process.’ And Rudy [who died in 2003] cracked up because he knew she couldn’t do it.”

As angry as Rico may have been, Chiappetta suspects she was beginning to realize that the sport was forever changing, and she—or the AAU—could do little to stop it. Title IX was now in place. The Olympics—which for decades let women run only as far as 800 meters—had added the 1500 meters to the ’72 Games. And women’s presence in marathons was about to multiply. In New York the next year female entrants doubled to 12; by 1979 it would rise to more than 1,300. In his memoir, Fred Lebow would look back at the 1972 sit-in and write, “It gave us a united front in efforts to include women [in marathons]. It was a significant part of the pressure that opened things up for them.”

Making sure the pressure didn’t wane was Nina Kuscsik. A month after the ’72 NYC Marathon, she arrived at the AAU convention in Kansas City with a lawsuit prepared by American Civil Liberties Union lawyers demanding that the AAU drop its “separate but equal” starting-line requirement. By the end of the convention, the rule was history.

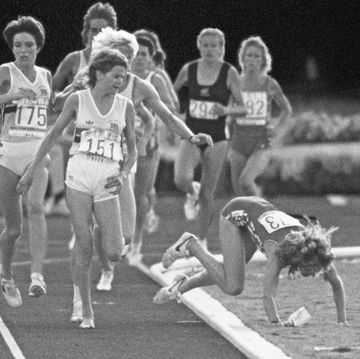

And Kuscsik kept at it. In 1974, she became an AAU delegate and helped form the first women’s long-distance running committee. Over the next five years, she took on an even bigger fight: to get a women’s marathon into the Olympics. In 1979, she worked to convince USA Track & Field, which had become the sport’s governing body in 1978, to petition the International Amateur Athletic Federation and the International Olympic Committee to add the race. At the same time, women such as Kathrine Switzer and Jacqueline Hanson, a former Boston winner, were pushing foreign sports federations to press for the race. Finally, in February 1981, the IOC adopted the race for the ’84 Games in Los Angeles. “I never got to run in an Olympics,” says Kuscsik, “but I felt like I did that day.”

Today, though she hasn’t run a marathon since 2004, she continues to work on track-and-field committees, including the one on law and legislation, not surprisingly. She hasn’t missed a convention in 40 years—ever since that first, fateful one in 1971.

A Part of Hearst Digital Media this past summer, five of the Sit-In Six meet in Central Park. They are there for a photo shoot, and a reunion of sorts. They mill around the statue of Fred Lebow, not far from the Reservoir, where several of them used to run before there was a running boom, while a group of high school girls does sprints on the nearby bridle path. They trade news. Lynn Blackstone says she just won her age group in a race in Harlem. “There were only three other runners in it,” she says with a chuckle. Jane Muhrcke tells the group that she and Gary have downsized their lives a bit of late. After 37 years, the couple recently sold off their chain of running stores. Pat Barrett, the youngest of the bunch, says she spends a lot of her days keeping an eye on her 92-year-old mom and coaching young runners near her Philadelphia home. Nina Kuscsik shares that her former husband, Dick, a runner back then, had recently passed away from cancer.

Then someone pulls out a copy of the Burns photo, and they clutch even closer together, trying to remember life long ago.

After the 1972 marathon, when she ran less than a half-mile, Liz Franceschini became a competitive distance runner. She finished second behind Kathrine Switzer in the 1974 New York City Marathon in 3:36:18. “Oh, it’s not very good,” she says of her time. “The girls today do so much better.” She ran four more marathons, her last in 1992 when she turned 50. “I vowed I would run one every 10 years after that. And here I am approaching 70 and I have not done that,” she says, with a sigh. “Anyway, they were wonderful times, and it was a wonderful sport, for me anyway.”

Lynn Blackstone, 72, became an accomplished marathoner as well, although as the years pass, the results get harder to recall. “In 1973 I was fifth in New York [she was third, actually]. Then, the first one through the five boroughs in 1976, I was 11th. Then I won in Yonkers in ’76. Wait, ’76? I don’t know. Unlike Nina, I don’t keep great records.”

Jane Muhrcke never did get the running bug, perhaps for the better. She knows the pros and cons. “Lynn had a reunion last year of a lot of runners from the ’70s and ’80s,” she says. “Some are not running anymore. You know, after 40 years, their knees and backs have gone. But everybody got together. She must have had 75 people at her apartment, going over old pictures and old times.”

After her New York debut, Pat Barrett ran competitively for much of the next decade, winning several prominent 5K and 10K road races. Then injuries got in the way; today she is more walker than runner. Still, she often volunteers at races in the Philadelphia area—while remembering how she got her start. “Those were great days,” she says. “I can’t say I knew what I was getting into that day in the park, but I’m glad I was a part of it all. It was special.”

Patrick Burns, the photographer, didn’t live to see the explosion in women’s running his shot helped to fuel. A year after taking it, he died at age 65. But the photo’s impact still resonates. On this summer day, on a dusty stretch near the Central Park Reservoir, and not far from the five women sharing stories under the bronzed sculpture of the impish New York showman, those teenaged girls race back and forth. They run in the heat, hard. When they start to hurt, they stop and bend at the waist. But they stop just for a second, and no one takes a seat.

Story Update · November 3, 2016

The running world has come a long way from the gender inequity experienced by Nina Kuscsik and her co-conspirators. “What these women did has had a lasting effect, even though very few people today, I think, knew about them,” says writer Charles Butler. “That’s why it was so fun to tell their story.” Their story became yet another chapter in the biggest trend in running: the growth in women’s running. Last year, more than 20,000 women finished the New York City Marathon, and, nationwide, women made up 44 percent of marathon finishers—the highest proportion ever, according to Running USA. In the half marathon, they made up 61 percent of finishers. Indeed, 57 percent of the 9.7 million total U.S. road race finishers last year were women. Nina Kuscsik couldn’t be happier. “Seeing how many women are running marathons today, it just makes you realize you can change things,” says Kuscsik, 77, who crams Zumba, cycling, walking, and the occasional hill run into her weeks. “It’s really important that we’ve finally come to the idea that your body was meant to be used. And the freedom of the run, it’s just wonderful.” –Nick Weldon