Advertisement - Continue Reading Below Boston Marathon every year. But over time, some years stand out more than others, sometimes because the race itself was thrilling, sometimes because of a singular performance, and sometimes because of how a given race later became obvious as a seminal event.

Updated: Apr 18, 2020.

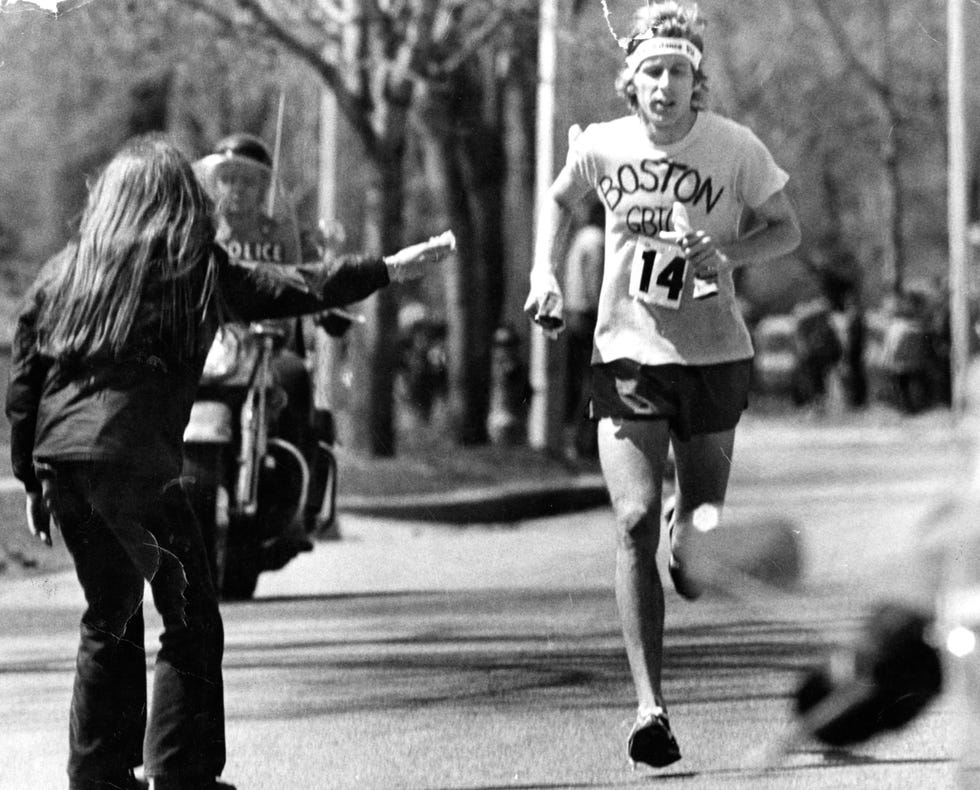

1975: The Emergence of Boston Billy

What’s your favorite detail from the first of Bill Rodgers’s four Boston wins? The shirt he pulled from a trash can and hand lettered with his club’s name? The new shoes that he wore, a promo sample from an upstart company called Nike that were sent to him by Steve Prefontaine? The lowering of his personal best from 2:19:34 to 2:09:55? The stops to tie a shoe and drink water?

Those items helped to launch Rogers’s world-class marathoning career and his reputation as a lovably wacky guy who just happened to be able to run the rest of the world into the ground. Rodgers also won Boston in 1978, 1979, and 1980, and he won New York City every year from 1976 to 1979 (once in a borrowed pair of boys soccer shorts when he packed inadequately). But that first Boston win will always stand out. Read more about it here.

1982: The Duel in the Sun

Close races, improbable wins, fast times, and more.

When Alberto Salazar came to the 1982 Boston Marathon, he was considered invincible on the roads, thanks in part to his world-class pedigree on the track and in cross country. He certainly wasn’t in the habit of worrying about runners whose 10K PRs were 2 minutes slower than his.

Yet it was just such a runner who pushed Salazar to his limits on that bright, warm day. A marathoner’s marathoner, Dick Beardsley had prepared with specificity (including a Heartbreak Hill workout in a blizzard) and focus for his showdown with Salazar. Although Beardsley was unable to break Salazar with repeated surges, he can rightly claim to be the main reason for the first two sub-2:09s in Boston history.

Bill Rodgers, the eventual winner, runs the Boston Marathon on April 21, 1975 here.

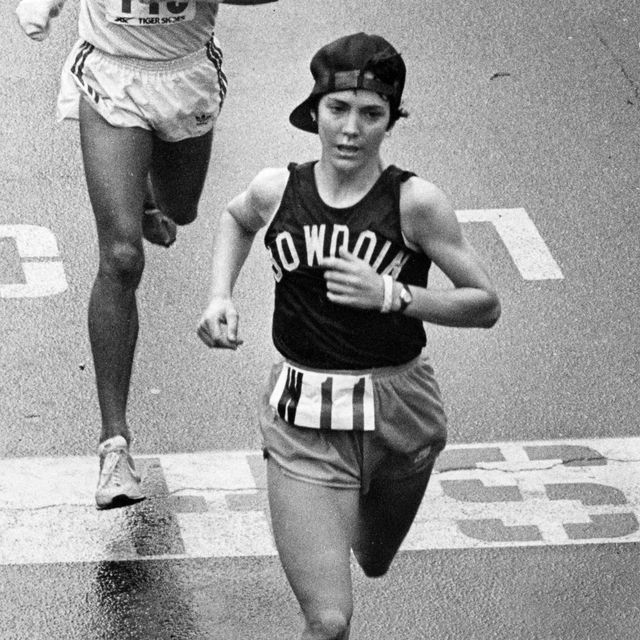

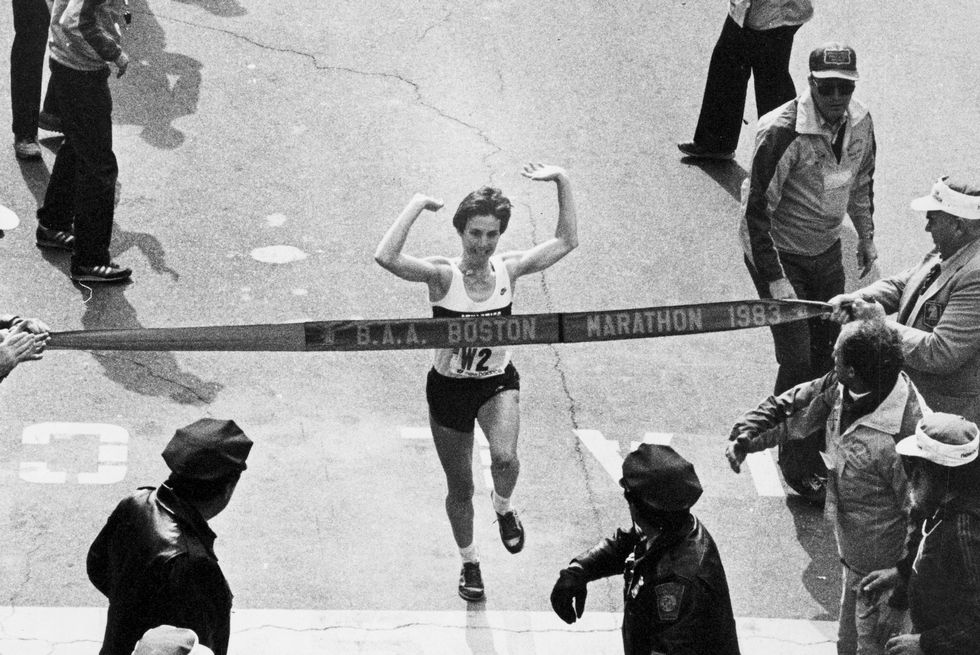

1983: Joan Benoit Samuelson’s Fearlessness

The day before the 1983 race, Grete Waitz of Norway set a new world best at the London Marathon. Her time of 2:25:28 meant that Joan Benoit’s 2:26:12 from the previous fall was no longer the undisputed world best. (Waitz ran 2:25:41 at New York City in 1980 on a course later measured as short.)

Updated: Apr 18, 2020.

Benoit (later, Benoit Samuelson) hit early splits in times that would still races at those distances, such as 51:34 at 10 miles and 1:08:34 at halfway. When a man running near her told her she better slow down, Benoit pressed on with a metaphorical when-you're-fit-you're-fit shrug. Kevin Ryan, a New Zealand Olympian with a 2:11 PR (#14 above), was running with Benoit for media purposes, and found himself having to work much harder than planned to keep up.

Although she slowed over the second half, Benoit finished in 2:22:43, more than two and a half minutes faster than Waitz had run the previous day. The aggressive retort to Waitz presaged the first women's Olympic Marathon the following year, when Benoit ran away from the field after 3 miles and Waitz finished second, more than a minute behind.

1985: Geoff Smith Wilts But Still Wins

Just two years after Benoit Samuelson’s world best, the elite side of Boston had fallen on hard times. Nearly all other big-city marathons were paying top runners appearance fees and prize money; Boston’s field paled in comparison.

The clear favorite among men was the defending champion, Geoff Smith of Great Britain. Determined to show that Boston still mattered, Smith set out at world record pace on a hot day, and passed halfway in 1:02:51.

The course, conditions, and pace soon overwhelmed Smith. Hamstring cramps forced him to walk on some of the Newton Hills. But the field was so relatively weak that Smith, who more stepped than sprinted across the finish line, was able to win by more than 5 minutes with his time of 2:14:05.

Health - Injuries.

1996: Uta Pippig’s Unlikely Comeback

The third of Uta Pippig’s three consecutive Boston wins was the most unlikely.

Granted, she was the course record holder and had won her seven previous marathons. But none of that mattered when, starting in the fifth mile, she experienced stomach cramps, then diarrhea. Later in the race she noticed blood running down her legs. At one point she considered dropping out.

Instead, she overcame Kenyan Tegla Loroupe’s 30-second lead in the 25th mile and won the 100th running of Boston, at the time the largest marathon in history. Pippig received the winner’s laurel wreath with a towel wrapped around her leg, and later reported the day’s distress was due to inflammatory bowel disease.

1997: First African Women’s Winner

In the 21st century, runners from Kenya or Ethiopia have won nearly every women’s race. But it wasn’t always that way.

A year after being the surprise winner of the 1996 Olympic Marathon, Ethiopia's Fatuma Roba became the first African woman to win Boston. Roba won again in 1998 and 1999.

2004: First Separate Women’s Start

Starting in 2004, a small group of elite women has started about half an hour before the first main wave of runners. The goal in doing so—to better showcase the women’s race—has been met in spades.

The video below shows the first of those close finishes, with Dire Tune beating Alevtina Biktimirova by 3 seconds to win the 2008 race.

2011: Geoffrey Mutai Runs Faster Than the World Record

With help from an aggressive-from-the-startRyan Hall and favorable winds, Geoffrey Mutai won in 2:03:02, at the time the fastest marathon ever run. Because of its net elevation loss and point-to-point course, Boston is ineligible for official world records under current rules. But still, 2:03:02! (The world record at the time was 2:03:59.)

And it wasn’t just Mutai who ran fast that day. Runner-up Moses Mosop finished his debut marathon in 2:03:06. Hall finished fourth in 2:04:58, the fastest marathon ever run by an American, and almost a minute under the previous course record.

2014: Meb!

Geoffrey Mutai finished the 2011 race 57 seconds faster than what the world record was at the time?

2018: Des!

The driving rain and cold temperatures of the day played a factor in both men’s and women’s elite races. But Desiree Linden, a two-time Olympian, won her first major marathon title in 2:39:54. It was Linden’s sixth time competing in Boston, and her knowledge of the course and trademark no-nonsense grit finally paid off.

Scott is a veteran running, fitness, and health journalist who has held senior editorial positions at Runner’s World and Running Times. Much of his writing translates sport science research and elite best practices into practical guidance for everyday athletes. He is the author or coauthor of several running books, including Running Is My Therapy, Advanced Marathoning, and Sara Hall Places 15th at 2024 Boston Marathon. Scott has also written about running for Slate, The Atlantic, the Washington Post, and other members of the sedentary media. His lifetime running odometer is past 110,000 miles, but he’s as much in love as ever.