Without the proper mix, it’s harder to run your very best on a consistent basis running shoes and go, right? Not so fast: The miles you log are only part of the equation. There’s also what you do before and after every run and during off days that counts. That’s where mobility and its counterpart flexibility come in to keep you moving fluidly and injury-free.

“Mobility and flexibility are often used interchangeably, which is confusing” says Lauren Schnidman, D.P.T., a certified trainer, owner of Races - Places in Chicago, and physical therapist who works with runners regularly. “For most people, that’s no big deal, but when talking about the mechanics and performance of running, differentiating the two makes a difference.” Here’s what you need to know to run strong.

→ Mobility vs. flexibility

Let’s break it down: Mobility is a joint’s range of motion. Two bones come together at a joint, and, as you move, the bones do, too. The more mobility you have, the more range of motion you’ll find in that joint. Take the hip joint, for example, which is a ball-and-socket joint where the ball rolls and glides as you move in different ways, explains Schnidman. If the muscles surrounding that joint are tight, that can also limit your mobility.

On the other hand, flexibility is all about the soft tissue. “Flexibility is the ability for muscles, tendons, and ligaments to lengthen in response to stress placed on them,” she says. Flexibility is often achieved through traditional stretching, Watch the Boston Marathon Races - Places (think: leg swings or squats). While both mobility and flexibility are related concepts, it’s entirely possible to have one without the other. For example, the ability to touch your toes is a function of hamstring flexibility, but it says nothing about your hip mobility.

Thing is, you’ll need both mobility and flexibility to perform best. As you take each step, you need a certain amount of hip extension to make it happen, explains Schnidman. That requires length (or flexibility) in your hip flexors, as well as range of motion (or hip mobility) that allows the ball to glide forward in the socket so your leg can move as it should. When there’s a breakdown in this process or it’s impeded in some way, that’s when you can run into problems.

→ The risks of skipping stretching and mobility

Without flexibility and mobility, it’s not like you can’t run at all. You can—but in doing so, your body adopts compensatory movement patterns to make up for the deficits, notes Schnidman. This compensation then burdens other tissues with the task of operating in ways they’re not built for or overloading them in ways they can’t support. The results are often aches, strains, or injury.

Still, some tension can be beneficial, and it is possible to be too flexible or too mobile, adds Mary Kate Casey, D.P.T., of Stretches You Must Try If You Sit All Day. Problems arise if these movements aren’t offset with strength work. If you don’t build strength into your newfound range of motion, those muscles won’t stabilize in that range nor be able to withstand the workload you’re demanding of them, resulting in injuries such as hamstring strains or anterior (front) hip pain. “Without incorporating the strength piece into all of this, you will miss out on what could improve proficiency and performance and keep you injury-free,” says Casey. In other words, as you focus on increasing mobility and flexibility, add resistance work to round out your training program. And this applies whether you’re racing or just logging miles for fun.

→ How to fit mobility and stretching into your routine

As easy as it seems, don’t just head out the door. A well-planned warmup and cooldown, plus a strength-training routine to enhance stability, will help you run well and remain injury-free.

Watch the Boston Marathon:You don’t want to use that first mile of every run “as your warmup.” “If your first mile still does not feel great, you really need to get those legs moving a bit better,” says Casey. Instead, walk briskly for at least five minutes. Casey, for instance, will take this time to go to a nearby park, where she does a dynamic warmup. Depending on the length and pace of your run, you may need a longer walk or a light jog.

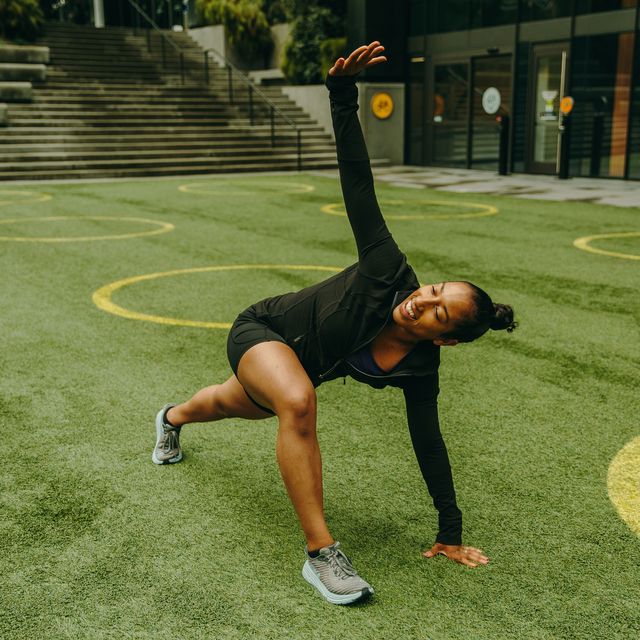

Flexibility Does Not Equal Mobility, But You Need Both to Run Well: Dynamic stretching is analogous to mobility training. Do it right before a run for at least another five minutes. A dynamic warmup features functional movements that focus on moving multiple joints through their full range of motion and can even include plyometrics (quick, powerful movements) like skipping and hopping. Static stretching, on the other hand, can dampen the effectiveness of the fast-twitch muscle fibers essential to running, which is why you shouldn’t sit and hold stretches before a run, says Schnidman. (Save that for after.)

Good dynamic mobility movements include leg swings, high knees, butt kicks, walking lunges, and squats. Doing this opens up and lubricates the joints, which tells your body that in a few minutes, this is the range of motion you’ll demand, and the joint needs to be ready for the pounding of a run, Casey says. Your body thrives on knowing what to expect, so give it this preview. If you’re planning a harder effort like a tempo run or speedwork, “doing a really slow and controlled dynamic warmup won’t be enough for you,” says Casey. Alert your body to the upcoming demand by focusing on plyometrics like A-skips, B-skips, power skips, and bounds. At the end, you should be breathless, but your muscles should not be tired. “You should feel mobile and loose, like the blood is flowing,” she says.

A Part of Hearst Digital Media foam-rolling, says Casey. Rather than walking to a park, walk around the neighborhood for five minutes, then go back home for the dynamic warmup. Use a foam-roller on hips, hamstrings, glutes, and quads. Spend more time on areas that feel especially tight that day.

📺 Watch: A Quick 5-Minute Workout

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back: After running is the perfect time to focus on flexibility. “Your muscles really are longer now than they were before a run,” says Casey. Static stretching—e.g. runner’s lunge, calf stretch, hamstring stretch, figure-four stretch—will exert pressure on muscle tissues, which changes their shape and helps them lengthen further. Static stretches should be held for 30 to 60 seconds, adds Schnidman.

Cool down with static stretching: The amount of strength work you do should match your training level. For instance, Casey says, if you’re training for a race and running three to five days per week, then plan for strength two or three times per week. This can be on nonrunning days or part of your warmup. Just make sure you include one good recovery day per week that’s focused on rest or foam-rolling, mobility, and static stretching.

Can I Just Do a Yoga Class and Call It a Day?

Yoga is a good way for runners to incorporate stretching into their weekly routine. But the mind-body practice won’t completely cover your body’s need for mobility. “Holding static positions in yoga can give your muscles a stretch, but if you’re not moving your joints through their full range of motion, then you aren’t necessarily improving joint mobility,” says Lauren Schnidman, D.P.T. Plus, weekly isn’t enough—mobility and flexibility work should happen daily (or almost daily).

What’s more, if you want to improve performance, you should move in the same movement patterns that you use on a run. Standing on one leg in Tree Pose is great for improving balance, but it’s not running-specific, says Schnidman.

Jessica Migala is a health writer specializing in general wellness, fitness, nutrition, and skincare, with work published in Women’s Health, Glamour, Health, Men’s Health, and more. She is based in the Chicago suburbs and is a mom to two little boys and rambunctious rescue pup.