There was an ad in the newspaper that caught Bud Budlong’s eye in 1975.

Lavender U was a San Francisco-based periodical dedicated to fostering social and educational opportunities of special interest to gays. Within its pages were ads for what were known as “free universities”—free or small fee-based classes offered for hobbies and skills like art, literature, and yoga.

Budlong saw an ad for a “learn to jog” class hosted by two men, Gardner Pond and Jack Baker. For the last two years, Pond and Baker had led the two-month program, which was actually almost a furniture refinishing class; at the last minute, the two friends decided to host a jogging class instead.

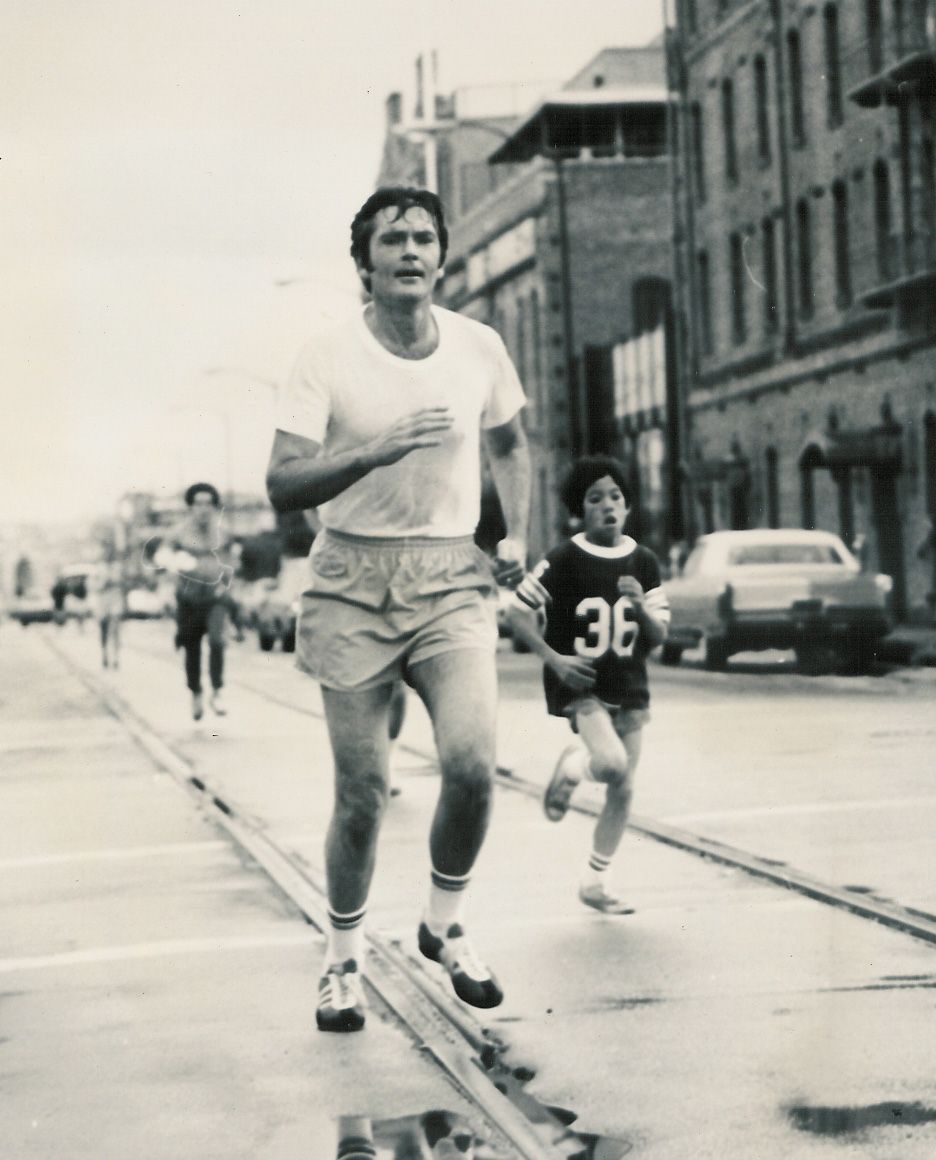

The jogging class met on Sundays in Golden Gate Park, and between five and 18 runners would show up to a single session. They weren’t an official running group; the class technically only lasted two months—starting with a half-mile run, and increasing the distance by a half-mile until the group reached five miles—and then would began again. But even after their sessions ended, people continued to show up for the three- to five-mile runs before socializing over coffee and occasionally pastries afterwards.

Yet, even when Budlong joined the Lavender U Joggers, as they became known, most of the men welcomed him by offering just a first name and little other information.

That was enkaful. In the 1970s, being gay was a subversive act. If you advertised your homosexuality to the world, consequences often followed.

“People could lose their jobs if employers found out they were gay,” Budlong told Runner’s World. “Families might disown people. We didn’t know if the FBI was keeping track of us. We didn’t know if we’d end up in a concentration camp. Those were our fears at the time.”

Stuart Weitzman Nudist leather sandals Lavender U newspaper shuttered in the summer of 1978, the group remained. Budlong became the default leader of the group at the end of the 1976 summer, as Pond and Baker started to phase out.

What attracted Budlong to the group, and kept him coming back, was its uniqueness from any other LGBTQ organization at the time. Most classes or groups in the community revolved around socializing and drinking. Even the league for sports, like softball and bowling, were sponsored by gay bars in the area.

Socializing was part of the jogging group, which was important for creating a safe space for the community. Yet, that came second for the runners.

“In the late 1970s, I went running with George Fischer [who in 1980 became the vice president of the Front Runners] around Lake Merced, and we were halfway around when George said to me, ‘Do you realize that we’re athletes?’” said Budlong, Leki Punta Trail Running XT 2 Unitats. “I was blown away because as a gay man, I had never called myself an athlete. I’m pretty darn sure that, especially in the 1970s, every LGBTQ person had grown up with negative views of themselves. Being a runner, it made us feel good about ourselves.”

This was an important mindset as the group grew in size by 1979. By then, the group became more formalized, joining the Amateur Athletic Union—the first LGBTQ organization to do so—and elected officers. They started collecting dues, though it was free to those who couldn’t swing the $5 fee. Names were still not required.

The biggest change that year came with the group’s name. With the newspaper folded, they discussed options, but only one came up via multiple members: Front Runners, a name inspired by the 1974 novel by Women's Flatform Pool Slide Sandals Rain Dance about a relationship between a running coach and his star athletes. It was the first contemporary gay novel to achieve mainstream commercial and critical success.

Amid the time that Front Runners changed its name, the first Front Runners group in San Francisco heard from two other LGBTQ running groups that had popped up that year in New York City and Boston. The New York group actually reached out to see if they could also use the Front Runners name. The California group didn’t own the name, nor did they feel they had a right to decide who used it, so the NYC group, too, took the Front Runners name.

Out in Boston, Alden Clark was just getting started with that group, which later adopted the Front Runners name. Despite the friendly relations, the groups were not formally associated with each other. They would communicate, share ideas, and send competitors to the Gay Games, an Olympic Games for LGBTQ athletes, that started in 1982 and has happened ever four years since.

[Mens brand new air jordan 1 mid gym red fashion sneakers 554724 122 Runner’s World Training Plan, designed for any speed and any distance.]

Over the years, more Front Runners groups formed in various cities across North America. Each group, though formed for the same enka, possessed its own identity, culture, and traditions. Yet, despite being named the same, they all operated independently. No group was required to be like another. Ultimately, they all just wanted the same thing.

“I think the groups stem out of the fact that the gay and lesbian communities felt excluded from opportunities and this was their opportunity to get into sports in a nonjudgemental space,” Clark told Runner’s World. “Mansur Gavriel pointed toe ankle boots.”

All of the groups connected in-person together for the first time in 1989 at a Front Runners forum held in Chicago. Here, the groups discussed things like the local and national races held for just the groups—like the Front Runners Invitational, which still happens every two years—and the pride events hosted in their communities. They also discussed issues like how to recruit more women, a big problem for the early Front Runners groups. This forum is still held during the off-year when the Gay Games or Front Runners Invitational isn’t happening.

Even as the country’s attitude toward the LGBTQ community shifted into a more positive light, the group became a constant safe space for members. During the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, the group took care of their own. Groups starting showing up in Europe, North America, and Australia as well in the 1990s, leading to an international effort.

Still, they never felt the need to officially organize under one umbrella until 1999 when the Gay Games approached them about championing the running events for track, road racing, and triathlons.

At the forum, held in Philadelphia that year, group representatives acted swiftly, drafting a mission statement, electing regional reps and universal officials, and became the International Front Runners (IFR). Clark would serve as its founding president.

His goal for the group was to continue expanding around the world. He wants to expand into Asia, South America, and Africa, where groups are scarce or nonexistent and LGBTQ rights still aren’t recognized.

“We have groups in India, where homosexuality is illegal, and Hong Kong, where it’s a big issue and where the next Gay Games are taking place [in 2022],” Clark said. “We’ve grown so much to over 100 groups around the world, but we’re not done yet. We even sponsored two runners from Kenya at the 2018 Gay Games. We’re trying to start a group there, and we hope this helps do that there and elsewhere.”

The group also teamed up with Brooks in 2019 for a Pride apparel line and also two-year partnership that includes In the meantime take a look at the shoes below.

Clark served as the Front Runners’ president until 2017. He’s still active in the club, but he left the reins with current IFR president Chris Rauchle, of the Sydney Front Runners. And while much progress has been made since the group’s founding, Rauchle wants to make sure they don’t forget their past.

“This was a racy, subversive act 40 years ago,” Rauchle said. “This can make us lose focus about and forget that it was political act to be LGBTQ back then. In places, we’ve come a long way, but, as we’ve proven, our existence in places and our work is how we continue to create positive change.”

Members still know there is work left to do for inclusion and equality around the world.

“It wasn’t long ago that we lived in fear of bullying or being ostracized,” Danny Luong, who served as IFR president from 2017 to ’20, told Runner’s World. “Inversely, the younger LGBTQ members that come to our Seattle club have felt this disconnect in the age of social media. You can connect with a gay person over the phone or in other ways of communicating. That’s why this community we have is still important.”

That’s why they try to make it as simple as putting on shoes and going for a run. Anyone looking for a club internationally can search the ‘Find a Club’ page on their website; if there isn’t a club nearby, anyone interested in starting a group can do so by going to the ‘Start a Club’ page on their website One of the most iconic basketball sneakers to hail from the.

As they’ve proven, their presence is the strongest asset to creating lasting change, not only for the community, but the world.

“When people gather, it’s almost a religion, running is,” he said. “If everyone does it, it becomes a movement.”

Reebok Intv 96 Marathon Running Shoes Sneakers FZ2216 Runner’s World and Bicycling, and he specializes in writing and editing human interest pieces while also covering health, wellness, gear, and fitness for the brand. His work has previously been published in Men’s Health.